The Spode Story

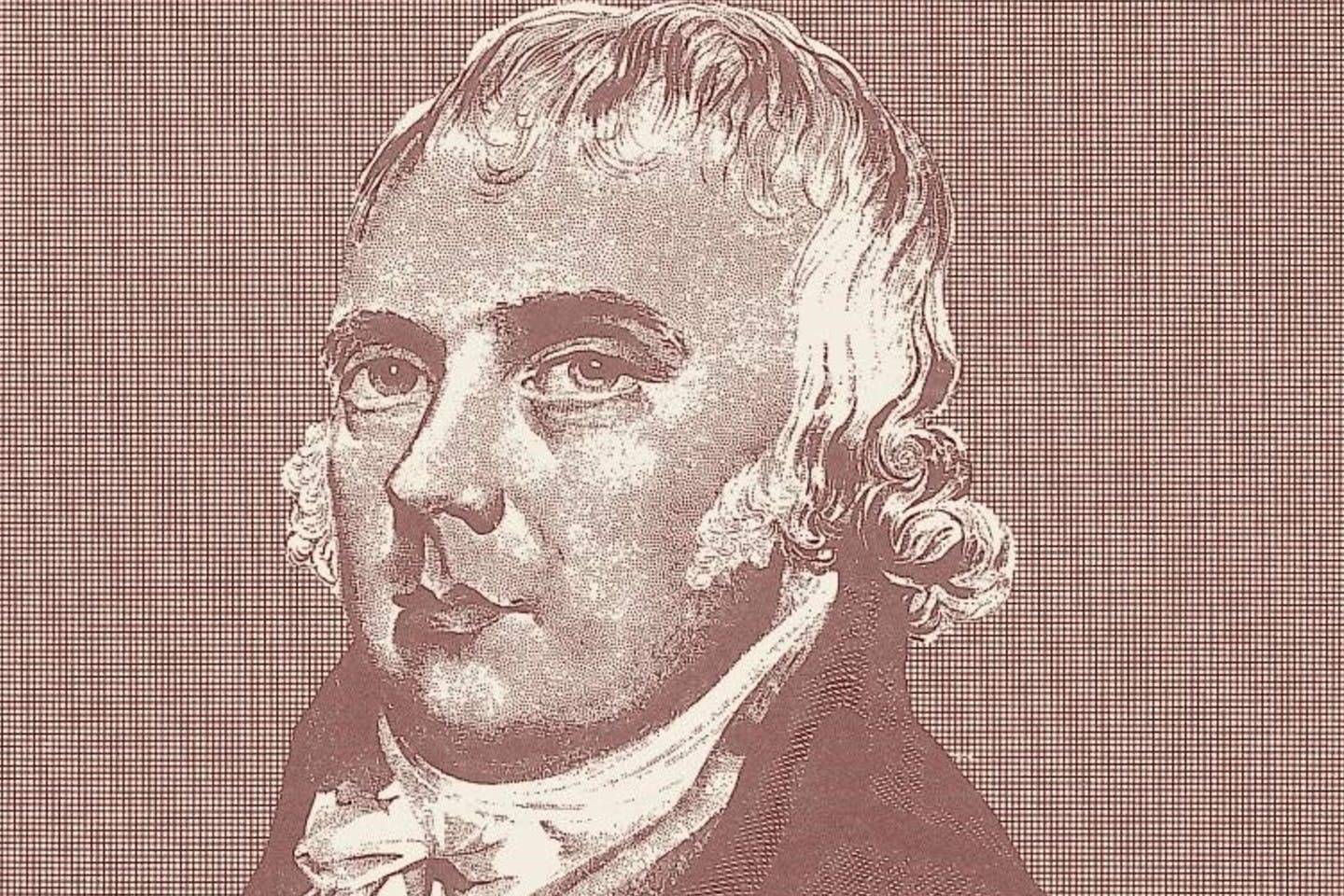

The Spode name is one of the most well-known of the Industrial Revolution. The eponymous Josiah Spode spent his early working years honing his craft with local potters, before establishing his own company in 1776 on Church Street in Stoke.

Just like his neighbour and good friend Josiah Wedgwood, Spode focused on the production of ceramic wares of the most exceptional quality.

Early Years

Josiah Spode I was born in 1733 in Staffordshire to a family of skilled potters.

After deciding to move into the family profession, Josiah worked as an apprentice for the eminent potter of his day, Thomas Whieldon, from the age of 16 to 21. Whieldon’s endless curiosity and willingness to experiment had a profound impression on the young Spode, and from there he worked in several partnerships until he took a position as the head of the Works of Turner & Bank in the 1760s.

In 1776, he was able to purchase property in the Church Street area of Stoke and take title to the entire Works of Turner & Bank, which became known as the Spode works and would remain as such until 2008.

Spode’s early products included creamware, pearlware and a range of stylish stonewares, such as black basalt, caneware and Jasper – which were similar to the famous namesakes that had been popularised by Wedgwood.

Revolutionary Processes

Blue Transfer Print Underglaze

Spode is credited with the perfection of blue transfer print underglazing; first seen on earthenware around 1783 or 84. Royal Worcester and Caughley had started transfer printing underglaze, and overglaze on porcelain in the 1750s, and from 1756 onwards, overglaze printing was also used on earthenware and stoneware.

The process for underglaze and overglaze decoration was very different. Overglaze on earthenware was actually a relatively straightforward process, and designs in colours of blacks, reds and lilacs were produced.

Underglazed, hot-press, printing was limited to the shades that could resist the temperature of the glaze firing, and a brilliant blue colour was the preferred option.

To upgrade this process from small teaware to larger dinnerware required the invention of a more flexible transmit paper to move the designs from the copper plate to the body of the earthenware. This brought about the development of a glaze recipe that produced a perfect black-blue cobalt print.

Spode employed two of the most skilled pottery artists of their day in engraver Thomas Lucas and printer James Richard, both of whom had worked in the Caughley factory during the early over and underglaze experiments. Alongside Thomas Minton – another Caughley-trained professional who supplied them with the copper plates – Spode was able to introduce the signature blue printed earthenware to the market.

The Spode method consisted of engraving a design into a copper plate, which could then be printed onto gummed paper. The coloured mixture was then worked into the etched areas of the copper plate and then printed by passing them through rollers.

These designs, including edge-patterns, had to be worked in sections, and were cut out and affixed to the fired ware – using a white cloth made of gum solution – and washed with water, which left the pattern attached. After one final dip in glaze, the pottery is returned to the kiln for glost firing.

Bone China

During the 18th Century, many prominent British potters were competing to discover the formula for the production of translucent porcelain. Many companies, including New Hall, were producing hard-paste porcelain similar to famous Oriental porcelain. It wasn’t until the 1740s that Thomas Fry introduced the use of bone ash.

Spode perfected the technology and by using 50% bone ash, 25% Cornish stone and 25% Cornish china clay, he was able to create a ceramic which was very easy to fire using the same factories and furnaces used to produce the earthenware.

Bone porcelains, particularly those of Spode and contemporaries Minton and Coalport, eventually established the definitive standard of soft-porcelain, the techniques for which were used widely for years to come.

Josiah Spode II & The First Copeland

Josiah Spode I died in 1797, which meant that Josiah Spode II was to continue in his place and refine his father’s processes.

In partnership with London banker and tea merchant, William Copeland, Josiah II ran the business for the next three decades. During the ‘Golden Age’ of English ceramics in the 19th century, the company expanded to become the largest pottery in Stoke and an expert manufacturer of pottery of all kinds.

Post-Josiah Spode

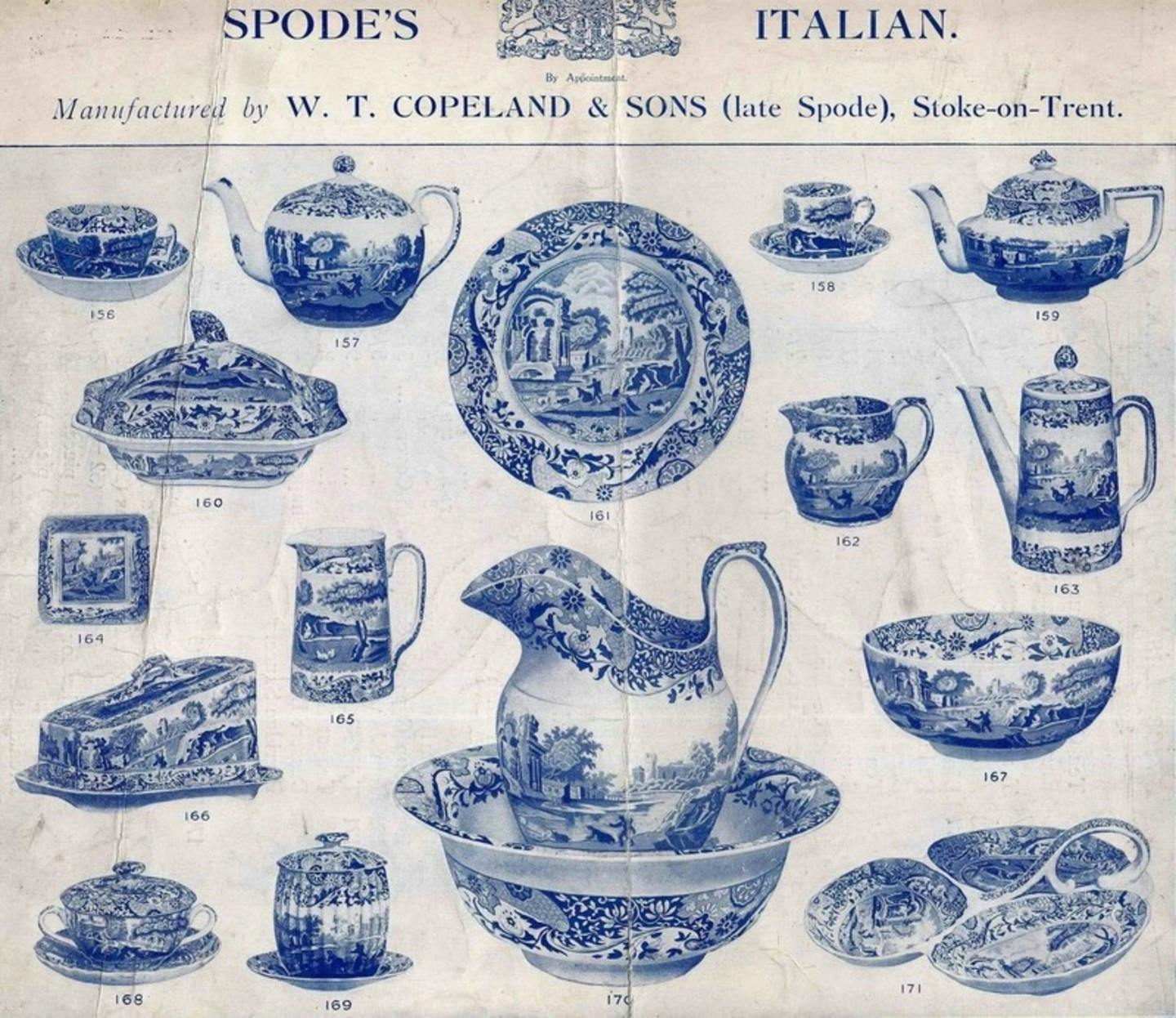

William Copeland died in 1826, followed by Josiah II two years later. The company passed through the hands of several managers, including one of Spode’s sons, until 1833, when William Taylor Copeland – William Copeland’s son – acquired the business with Thomas Garrett.

From 1833 to 1847, the company traded under the name of ‘Copeland and Garrett’ which specialised in fashionable rococo style products.

In 1846, William Taylor Copeland took complete control of the business, which stayed within the hands of the Copeland family for four generations until 1966.

Under the leadership of the Copelands, the company was to compete toe-to-toe with Minton in making some of the most beautiful ceramic creations of the era. Talented artists, such as C.F. Hurten, were brought in from continental factories and the best pieces were displayed during the Great Exhibition of London in 1851 and two further International Exhibitions in London and Paris, during 1862 and 1878 respectively.

Twentieth Century

By 1900, the company had been owned and run by the Copeland family for 67 years. After World War I, dinner and tea sets were high on the list of priorities for young homeowners, and massive quantities were made at various price points.

A large number of transfer prints were produced during this time; often variations of patterns first seen during Josiah II’s time in charge, but on a much larger scale.

Some of these products were some of the most popular the industry has ever produced and are still found on the shelves of passionate collectors even now. Chinese Rose, India Tree, Italian and Christmas Tree were hugely popular.

The company also produced Art Deco and modernist styles in the 1930s by recruiting sculpture Erik Olsen, who was able to capture the taste of the time along with new patterns and modern techniques.

Spode continued to produce the most beautiful bone china in the world by maintaining the specialised skills of its employees and investing in new manufacturing processes to ensure they were always a step ahead of the competition.

The company passed out of Copeland family hands in 1966, after over 120 years of sole ownership.

Changes in the Industry

From 1966, the company was owned by numerous hierarchies, before being merged with Royal Worcester.

The latter part of the 20th Century saw significant advancements in ceramic decoration. Traditional skills and techniques, where Spode was traditionally at the forefront, were suddenly obsolete. The highly specialised engraving technique was no longer time or cost efficient and could be easily replicated by computers, which produced digital designs of comparable quality to their hand-crafted counterparts.

Advancements in lithographic printing meant that full-colour images could be transferred onto a product and fired during a single session.

Spode continued to maintain small teams of traditionally skilled workers, including engravers and painters, in fact, some of the famous Royal Worcester and fruit patterns were hand-painted in the Spode factory in Stoke.

As well as introducing the commemorative collections, the company released classic patterns like Stafford Flowers, Woodland, Trapnell Sprays and the Blue Room collection, which reproduced blue-printed designs from the previous century.

During the 1990s and 2000s, much of the production of ceramics by the British pottery companies were relocated to the Far East, including Spode. In 2009 the business was bought by the Portmeirion Group, who returned much of Spode’s production back to their own factory, which sits just a few hundred yards from Josiah Spode’s original works.

Modern Era

These days, some of the most popular patterns, including Blue Italian, Woodland, Christmas Tree and the Blue Room Series are still in production. New patterns such as Delamere Rural and Pure Morris have been designed with one eye on contemporary design and other on the history that has inspired nearly 250 years of Spode.

For more information about anything we’ve covered in this blog, contact us today or visit our Kenilworth showroom to view our extensive product range, which includes new and replacement Spode chinaware.

GBP

GBP